FINRA Cites Pennystock Sales By Feltl Rep While Customers Buying

March 10, 2017

If you wet your finger and hold it in the air, you can feel the change in the direction of the wind flowing from the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority. With the ascension of new Chief Executive Officer Robert Cook, change is in the air. At first blush, it's a nice, steady breeze.

Some call me FINRA's leading critic. Others call me an annoying gadfly. Others (mainly my wife) call me a pain in the ass. There's probably merit in all three characterizations. That being said, I have taken my service as a long-time critic of Wall Street self-regulation and of NASD and more recently FINRA as a badge of honor. I have battled long and hard against the pernicious influence of too-big-to-fail FINRA member firms and I persist in championing smaller member firms and the individual men and women who labor in our biz. At my core, I am a staunch advocate for industry reform, a critic of mandatory customer and intra-industry arbitration, and an unrelenting proponent of fair regulation and commonsense.

Maybe, just maybe, FINRA CEO Cook and I can bury the hatchets. Unfortunately, I've seen the new brooms before. They sweep clean at first. Then they get put away and the steamrollers come out to pummel the small fry and to level all opposition. I've managed to avoid becoming part of the pavement for many years. I intend to remain light afoot for now.

In that spirit, today's BrokeAndBroker.com Blog is complimentary of a FINRA regulatory settlement and the helpful advice that it offers. My commentary also includes yet another diatribe about counter-productive FINRA policies and practices. Reform often moves at a glacial pace. You can't always see the progress but it's there. Let's see how much further things move after this column makes the rounds at FINRA: I'm guessing that a few more darts get thrown into the dartboards with my face on it.

Case In Point

For the purpose of proposing a settlement of rule violations alleged by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority ("FINRA"), without admitting or denying the findings, prior to a regulatory hearing, and without an adjudication of any issue, Feltl & Company submitted a Letter of Acceptance, Waiver and Consent ("AWC"), which FINRA accepted. In the Matter of Feltl & Company, Respondent (AWC 2010024882202, February 28, 2017).

Feltl has been a FINRA member firm since 1975 and presently maintains eight branch offices with about 98 registered individuals.

Penny(stock) for Your Thoughts?

Featured in the Feltl AWC are the exploits of one of its registered representatives - in fact, FINRA's regulatory case is largely built on this one rep's conduct and Feltl's allegedly deficient supervisory system.

SIDE BAR: Despite that nexus, FINRA hides the identity of the rep behind the initials "TC." Ah yes . . . another round of FINRA hide-and-seek! And another lost opportunity to promote investor protection and industry reform. Why does Wall Street's self-regulatory organization persist in this misguided protocol of protecting the guilty? It's a legacy issue that I don't understand and have long argued against. As you will see at the end of this article, there are compelling reasons for either the disclosure of TC's name, or, at a minimum, his prior FINRA regulatory settlement should have been referenced by link or docket number in the Feltl AWC.

According to the Feltl AWC, during the two-year relevant period from October 1, 2008, through October 26, 2010:

Not So Exceptional Exception Reports[TC], a registered representative associated with the Firm, sold more than 900,000 shares in X Corp., a penny stock that he personally owned, at or around the same time he was recommending to his Firm customers that they purchase shares in X Corp. TC sold his X Corp. shares through a Firm account held in his own name. During the Relevant Period, 59 of TC's Firm customers purchased approximately 1.27 million shares of X Corp. based on TC's recommendation.In several instances, TC sold his shares in X Corp. on the same date that one of his customers purchased shares in X Corp. pursuant to TC's recommendation. TC failed to disclose to his customers that he was selling shares in X Corp. while recommending that his customers purchase X Corp. shares. TC's association with the Firm terminated on October 25, 2010.

FINRA asserted that Feltl lacked a supervisory system and written procedures reasonably designed to appropriately monitor trading in its associated persons' accounts. In reaching that conclusion, FINRA noted that although Feltl exception reports identified same-date trades involving securities held by firm employees and customers during the relevant two-year period, those reports were:

primarily used to identify instances of "front-running." The exception reports were not designed to detect or monitor for conflicts of interest arising out of instances where a Firm employee was selling a stock that he was recommending that his customers purchase. The Firm had no other system or procedure in place that was principally used to detect or monitor for conflicts of interest arising from transactions in Firm employee accounts, or to ensure that appropriate disclosures were made to Firm customers.

Compounding the above shortcoming, FINRA deemed that the Feltl's Written Supervisory Procedures ("WSPs") did not discuss exception reports or the process for their review. Moreover, although the WSPs required Feltl supervisors to review daily trading blotters and periodically review employee-account transactions, the procedures provided inadequate guidance regarding the scope or nature of such reviews.

Y'all Color Blind?

Finally, FINRA found that during the relevant period, Feltl failed to timely respond to numerous "red flags" (such as disclosures on the firm's blotters) as early as April 2007 (about one to three years before the relevant period) indicating that TC was selling X Corp. shares while contemporaneously recommending that his customers purchase those shares. Taking all the above facts and circumstances into consideration, FINRA concluded that:

Sanctions[D]espite having these items of information available, the Firm did not take timely appropriate steps to monitor TC's selling activity or ensure that adequate disclosures were made to TC's customers.

FINRA deemed that during the relevant period, Feltl failed to establish and:

- maintain a reasonable supervisory system, including written supervisory procedures, to monitor and review for conflict-of-interest transactions executed in its associated persons' accounts; and,

- maintain and enforce written supervisory procedures that were reasonably designed to supervise the personal trading activity of at least TC.

Bill Singer's Comments

All in all, I like the content and context provided in the Feltl AWC and believe that it offers a treasure trove of useful advice to member firms about how they should monitor the trading at issue and offers useful guidelines aimed at enhancing supervisory systems. That being said, the Feltl AWC is not without its faults.

FINRA Hypocrisy

It is appropriate for FINRA to sanction a member firm for failing to connect the conflict-of-interest dots over a two-year period; however, it is just as fair to wonder where the hell FINRA's examination staff was during that same period. After all, if the so-called red flags waving wildly on Feltl's trade blotters clearly disclosed same-day sales by an associated person of shares that were being purchased by firm customers, how come FINRA missed that glaring anomaly? Moreover, let's keep in mind that the Feltl AWC is dated 2017 and the years during which those red flags were flapping around on the firm's books were in 2008, 2009, and 2010. How then does a self-regulatory organization not catch purported warning signs during three annual oversights? How does FINRA justify the apparent hypocrisy of wagging its finger at Feltl in 2017, which works out to between 7 to 9 years after the fact? The troubling and unsettling explanation is that FINRA isn't particularly effective when it comes to reviewing trading at its member firms but is particularly effective when it comes to gotcha regulation.

FINRA's full-time regulators missed the supervisory lapses that were clearly disclosed for three years on Feltl's books and FINRA's examination staff didn't do jack about the alleged violations for nearly a decade and FINRA has the audacity to censure and fine the member firm for facts that the self-regulatory organization also failed to catch?

Prior History

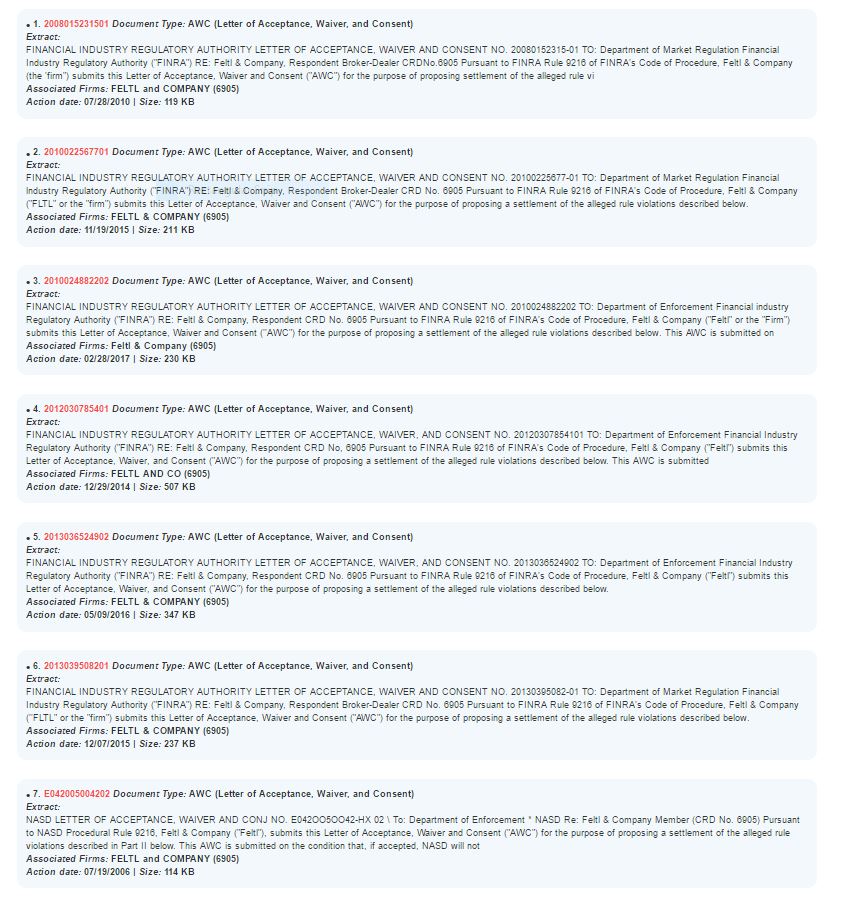

It is customary for FINRA AWCs to disclose so-called prior regulatory history for a settling respondent. Oddly, no such disclosure is provided for Feltl. Frankly, I don't understand this omission or the absence of an explanation by the self-regulator as to why no disciplinary background was provided in the AWC. If you enter "Feltl" into FINRA's online Disciplinary database, you get seven results as shown in the screenshot below. I'm not saying that all of the results are necessarily "relevant," but what I am saying is that the Feltl AWC doesn't even assert that there was any prior history, much less go through the exercise of parsing the relevant from the irrelevant. Next time you negotiate a settlement with FINRA, insist that your prior regulatory history is not disclosed in the published AWC:

Piercing FINRA's TC Veil of Secrecy

Finally, and I must note that I render this comment with both fatigue and disgust, FINRA has again seen fit to hide the identity of TC in the Feltl AWC. The Cone of Silence in the old Get Smart television series was a more effective device than FINRA's silly resort to initials. It took me less than one minute to uncover TC's identity and the underlying misconduct for which FINRA sanctioned him in 2014 -- three years before the Feltl AWC.

For the purpose of proposing a settlement of rule violations alleged by the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority ("FINRA"), without admitting or denying the findings, prior to a regulatory hearing, and without an adjudication of any issue, Thomas N. Charbonneau submitted a Letter of Acceptance, Waiver and Consent ("AWC"), which FINRA accepted. In the Matter of Thomas N. Charbonneau, Respondent (AWC 2010024882201, September 22, 2014).

The Charbonneau AWC asserts that he entered the industry in 1972 and became registered in March 2005. As set forth in the Charbonneau AWC:

In addition to allegations concerning Charbonneau's 2013 conduct at Berthel during which he purportedly caused a customer to sign blank investment forms, the Charbonneau AWC presents this pertinent narrative:[I]n a Form U-5 (Uniform Termination Notice for Securities Industry Registration) filed (October 26, 2010, Feltl reported that Charbonneau had been under-internal review for "conflicts of interest resulting from RR's liquidation of substantial amounts of [X Corp ] stock while at the same time recommending that his customers buy and/or hold that same stock." Rather than comply with certain conditions placed on him by Feltl regarding his trading of X Corp. stock, Charbonneau resigned from employment at Feltl,On October 28. 2010. Charbonneau joined Berthel Fisher & Company ("Berthel"). a FINRA regulated broker-dealer, where he was employed until November 2013 In a Form U-5 filing on December 2, 2013, Berthel reported that Charbonneau was discharged on November 13, 2013 for "allow[ing] a client to sign blank forms."

X Corp. is an issuer whose common stock was registered under Section 12(g) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 and quoted on the Over-the-Counter Bulletin Board ("OTCBB"). According to X Corp., it has developed a technology that enables it to more accurately determine whether human tissue is cancerous. X Corp. claims that the product has been used in two countries in Europe and in one country in the Middle East.X Corp. filed for bankruptcy in 2002. At that time, Charbonneau and his clients owned X Corp. stock and, in some instances, owned X Corp. bonds as well. Charbonneau attempted to salvage the company from bankruptcy. Another registered representative who worked with Charbonneau, RS, introduced Charbonneau to a venture capitalist named JH, who was also RS's step-father. JH, at the suggestion of Charbonneau, raised money through a rights offering and brought the company out of bankruptcy in 2004. Charbonneau received approximately 2.5 million shares in the re-organized company in connection with the rights offering, although he paid only about $20,000 in fees. As a result, the cost basis of those X Corp. shares was less than $0.01 per share. The 2.5 million shares of X Corp. constituted virtually all of Charbonneau's net worth, apart from his home. Charbonneau subsequently paid $140,000 to acquire an additional 1 million shares in a convertible preferred stock offering during the 2nd Quarter of 2009.During the periods that he was at Feltl and Berthel, Charbonneau sold a large number of shares of X Corp. from his own accounts. From October 2008 through May 2013, he sold approximately 1.7 million shares of X Corp., generating proceeds of approximately $400,000. He sold over 900,000 shares of X Corp. while employed at Feltl and over 750,000 shares of X Corp. while employed at Berthel.During this same period of time, many of Charbonneau's customers bought X Corp stock pursuant to Charbonneau's recommendation. In total, his customers bought over 5.2 million shares of X Corp. stock. Approximately 2 million shares were solicited by Charbonneau and purchased by his customers - 1.27 million shares by a total of 59 customers at Feltl from October 2008 to October 2010, and approximately 690,000 shares by 12 customers at Berthel from October 2010 to May 2013. While Charbonneau's cost basis for the majority of the shares he sold was below a penny a share, his customers paid significantly more for X Corp. stock at his recommendation during this period. From October 2008 through May 2013, X Corp. traded at a high of $1.77 per share on September 16, 2009 and a low price of $0.03 per share on October 5, 2011. Charbonneau did not disclose to these customers, however, that he was personally selling X Corp. stock while he was recommending that they-purchase X Corp. stock.There were approximately 13 separate trading days on which Charbonneau sold shares of X Corp. in his personal accounts at Feltl on the same day that one of his customers bought shares of X Corp pursuant to Charbonneau's recommendation Over the course of those days, Charbonneau sold a total of 120,800 shares from his personal accounts and bought a total of 201,465 shares for his customers' accounts. . .

In accordance with the terms of the Charbonneau AWC, FINRA imposed upon him a Bar from association with any FINRA member firm in any capacity.

Online FINRA BrokerCheck records as of March 10, 2017, disclose that on December 1, 2011, Charbonneau filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy, and the discharge was granted on March 6, 2012.

In conclusion, my point about the Feltl AWC's inane reference to "TC" is a fairly simple one. When you have a prior regulatory settlement or adjudicated finding involving facts that are relevant to a subsequent regulatory case, it makes sense to disclose the identity of the respondent(s) who had previously settled or were found guilty, or, in the alternative, to include a link or full-docket reference to the prior regulatory matter in the subsequent settlement document. If the "prior' matter is still pending and the presumption of innocence is vibrant, that's a whole other issue. Charbonneau settled with FINRA in 2014 for a Bar but his name is not disclosed in Feltl's 2017 AWC and there is no link or docket number reference in that latter settlement to the earlier Charbonneau AWC. The detriment of citing only to "TC" in the 2017 Feltl AWC should be obvious; the benefit of that obfuscation is obscure.